Tango blog

-

![]()

My DJ Journey Through Uruguay's Milongas

In April and May of 2023 I had the absolute pleasure and honour of DJ’ing at three milongas in Uruguay. While visiting my family I was kindly invited to DJ at Corazón Tango, a local milonga in Piriápolis, and two of the most renowned milongas in Montevideo: El Chamuyo and JovenTango.

All three experiences were incredibly positive, not only because I was surrounded by family and childhood friends, DJing in my city of birth, and the town where I grew up, were quite emotional experiences.

To be able to play the music that I grew up with to a local audience filled my heart with joy. It also made me incredibly nervous. Nerves are something that I am quite accustomed to, I liken DJing to performing – there is a lot of pressure on the DJ to ensure that everything runs smoothly and most importantly that the floor is full of happy milongueros doing their thing!

Corazón Tango at La Fontana, Piriápolis

The first gig came as an absolute surprise, I landed in Uruguay on 5th April and on the 6th I was DJing for Corazón Tango at La Fontana, never having attended the venue, nor knowing the crowd, their likes and dislikes, I had a lengthy conversation with the organiser to ensure that her expectations aligned with my experience and style of DJing.

This milonga doesn’t have a set entry fee, it’s strictly by donation, and at the end of the night the proceeds were split between the organiser and the DJ.

*I mention this and will mention DJ remuneration because I feel that it’s an issue that is often overlooked, DJs are sometimes expected to play for free, on a volunteer basis which does no favours to the profession and when taking into account the importance of the DJ as well as the hours of work involved (before and during the milonga) it doesn’t make sense.

JovenTango, Montevideo

The next gig was on Friday 28th April at JovenTango in Montevideo, a non-for-profit organisation created in 1977. I had already attended various milongas over the years at JovenTango, however, during the pandemic they moved to a new venue, so this venue was new to me. I decided to take a trip to Montevideo two weeks prior to get a feel for the new venue, the dancers, the style of music, and had a chance to meet the Director as well as the DJ for the night.

So on Friday 28th April I was ready to go with my DJing travel kit and my laptop. I was surrounded by family and friends as well as a fabulous crowd of milongueros, many of whom complimented my music selection during the evening. My heart filled with joy, never did I expect the feedback I received that night. In Uruguay payment of DJs is taken very seriously and at the end of the evening I was presented with an envelope as well as a logbook where I was asked to sign as proof that I had received my payment for the evening. While JovenTango is a not-for-profit they charge a fee for members and non-members.

El Chamuyo, Montevideo

My final gig was on Thursday 4th May 2023 at El Chamuyo. I had several conversations with the owner who was overseas at the time, as the venue and milonga were entirely new to me and I would not have the opportunity to attend one of their milongas prior to my gig.

I arrived early and set up in a booth that was higher than the level of the dance floor, the organiser’s daughter greeted me and set up my name at the DJ booth. This was by far my longest set, 5.5 hours and what turned out to be two distinct groups of milongueros throughout the evening which ended at 3am. The first group were an older crowd similar to that of JovenTango, but by around midnight the crowd changed entirely and now I was playing to a much younger audience who were very keen to dance until the early hours of Friday. Having two entirely different groups meant that I had to re-think my cortinas because it was quite clear that what I’d been playing for the first part of the night was not suitable for the second half of the evening. In terms of tango I didn’t alter my usual style of playing although I made sure to include Pugliese and some high energy D’Arienzo during the remaining couple of hours.

Reflections on the Role of a DJ

These experiences underscored the significance of a DJ's role in crafting the atmosphere of a milonga. Each organiser encouraged me to infuse my personality into the cortinas, reaffirming the DJ's creative influence. In Uruguay, the value placed on the DJ's contribution was both humbling and enlightening.

Conclusion: A Journey of Musical and Personal Growth

This tour was more than a series of gigs; it was a journey of personal and professional growth. It reinforced my belief in the power of music to evoke emotions and bring people together. As I reflect on these experiences, I am grateful for the opportunity to return to my roots and share my passion for music. This trip not only enriched my skills as a DJ but also deepened my connection with my heritage, an experience that will continue to resonate with me as I further my career.

Written by Beatriz Diaz for www.tangosuraustralia.com

14 Jan 2024

-

![]()

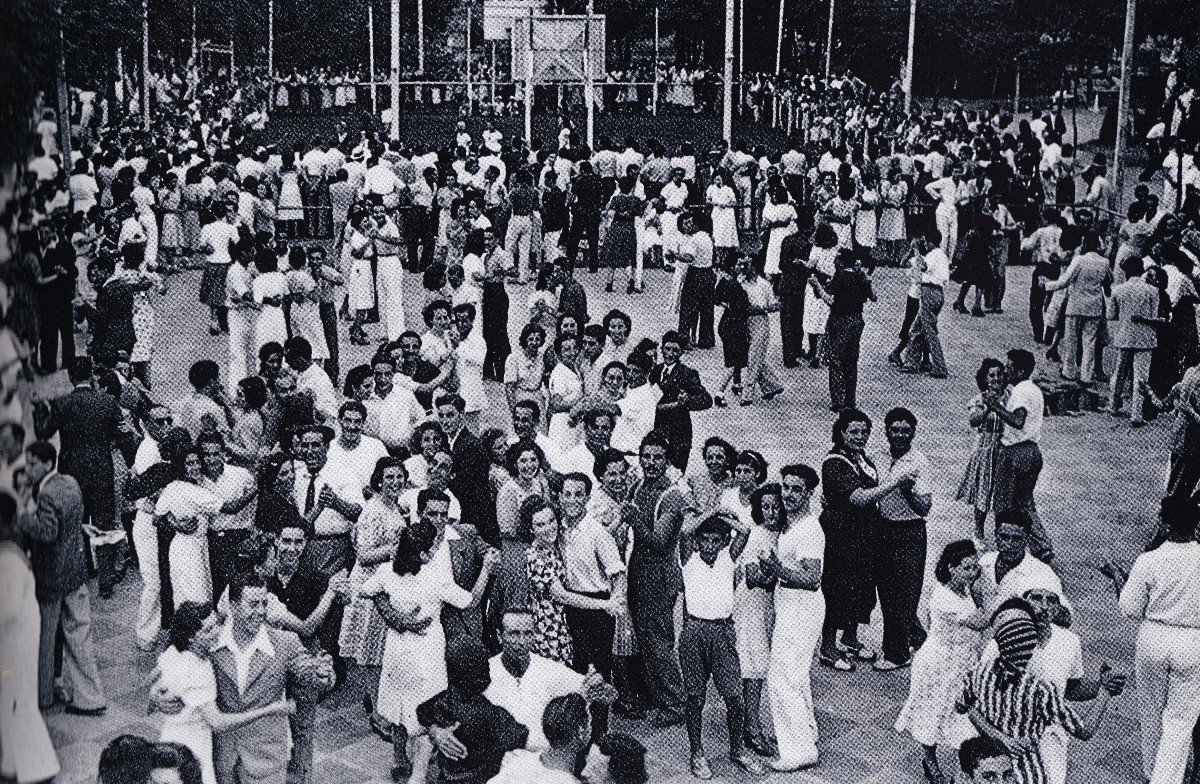

1933 film ¡Tango!

Over the last 3 months I’ve been undertaking a 6 month diploma course in the History of Tango organised by the Argentine Institute of Tango (Instituto Argentino del Tango) together with The Latinamerican Academy of Social Sciences (Academia Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales).

It’s been an interesting journey with a strong focus on historical facts that have been documented through iconography rather than word of mouth or history books. So far, so good, however, at the very outset we were warned by the teachers that much of the information being taught would be information that isn’t widely known or accepted by the tango community at large, and they even went as far as saying that in many cases this new information has not been accepted by Argentinean academia in general.

Their argument being that many of the historical books we read today are based largely on a handful of books that were written a century ago (or more) that were not based on facts, or that were based on incorrect information and therefore they cannot be relied upon, it is largely unfounded information and often based on the writers’ ideology or on hearsay.

In this pursuit for actual facts, we embarked on a lovely journey that has involved the study of a range of iconography from old street maps of the city of Buenos Aires, to magazines, newspaper articles, paintings, photographs, old recordings on phonograph cylinders, and films, to name a few.

Which brings me to the topic of the blog, and that is the 1933 film ¡Tango!

¡Tango! is a black and white Argentinean romance musical that debuted on the 27th of April 1933. Directed by Luis Moglia Barth, it was the first production for the film company that would later become ‘Argentina Sono Film’ and the first Argentinean film made using optical sound technology.

The film has a basic storyline and is a goldmine in terms of showing us what tango was like in the early 1930’s. I encourage everyone to watch it, it’s freely available on YouTube and is 1hr 15mins in length.

The cast includesTita Merello (Tita), Libertad Lamarque (Elena), Alberto Gómez (Alberto), Pepe Arias (Pepe el Bonito), Juan D’Arienzo, Luis Sandrini (Berretín), Juan Sarcione (Malandra), Azucena Maizani, Mercedes Simone, Edgardo Donato, Osvaldo Fresedo, Pedro Maffia, and many more.

When watching the film notice the handholds, the drinking mate at the milonga, arms often straight out, rather than in the embrace we are familiar with now (as per couple on the left).

Many of the women in the film rest their arm on the man’s shoulder, along the length of their arm, and sometimes on their chest. Observe the handhold.

You’ll notice an Orquesta de señoritas, there were several orchestras with female only musicians both in Uruguay and Argentina. Unfortunately there isn’t a lot of information available on this subject as there are few photos and possibly no recordings. However, it has been said that some (NOT ALL) of the female only orchestras were used for marketing purposes to attract male patrons to the venue and where ‘pretending’ to play as may be the case in this scene. I have also learnt that in Montevideo there were at least two locations where actual female musicians played frequently, one was Cafe Palace.

You’ll also see the sign for a Dance Academy that teaches tango with or without ‘cortes’. Tango without ‘cortes’ is tango that is simply walked. The moment the walk is interrupted in order to do a figure the tango is then referred to as having ‘cortes’, or ‘with cuts’. Dancing with ‘cortes‘ may also have implied that it was an improvised dance.

Do you recognise the violinist on the left? Juan D’Arienzo would have been 33 years of age here.

In the film we can see that the dance-floor was rather chaotic, there was no line of dance as we know it today.

More embraces… and who says you can’t enjoy a glass of wine or two at a milonga!

You’ll see Libertad Lamarque, and Osvaldo Fresedo and orchestra with a harp player. Fresedo would have been 36 years of age in the film.

As I said earlier, I encourage you to watch it, the music is captivating, as is the dancing, and see who else you can identify in the film. Enjoy!

Written by Beatriz Diaz for www.tangosuraustralia.com (first published September 13, 2021)

-

![]()

New York, Paris and Salerno: Tango without borders

One of the things I adore about dancing tango is being able to travel the world and not be limited by language, location, who I know, or whether I’m travelling alone. Once I hear the familiar music in the air the excitement sets in.

My latest trip was not a tango trip, however, my aim was to dance once at each destination and given that I travelled with a small carry-on suitcase for the entire month, I only allowed myself to pack two milonga dresses and one pair of dance shoes.

New York

My trip started in New York where I met up with a couple of non-tanguera school friends from Uruguay, both enjoy listening to tango so they were keen to go with me to the milonga. It was a Thursday night so we headed to La Nacional (239 W 14th St, New York) on a recommendation from a Sydney dancer. We hadn’t made a reservation and when we arrived, we were surprised to see that the room was full. It was a smallish rectangular room with a bar, a small area with tables, a stage, and chairs lined along the walls, and timber flooring. We pondered over the best place to put down our things, and ended up moving a couple of times, our final spot was on the chairs lined against the wall. We ordered some red wine and made ourselves comfortable.

The girl at the front desk was not particularly friendly but the leaders were lovely, I enjoyed some nice tandas. The cover charge was US $15 and included a performance by Lorena Gonzalez (Tango Salon World Champion 2014) and Gaston Camejo.

London

Next on the itinerary was London, this time I was on my own, my girlfriends continued on their trip to Miami whilst I crossed the Atlantic Ocean to London. I was only in London for two nights and given that I was too tired on the first night I left the dancing for the second night which in hindsight was a mistake because I ended up with a minor injury which meant I wasn’t able to dance at all. Incredibly disappointing but there was nothing I could do about it so I continued to enjoy the trip.

Paris

My next stop was Paris, I enquired with a tanguero about the best milonga to go to and was told to go to the outdoor milonga at Place de l’Opéra, on the stairs of Palais Garnier. I was a little worried as I got the metro and really wasn’t quite sure what I was going to encounter at the other end of the line, but I was delighted to hear tango in the air as soon as I exited the station. Actually, what I saw was the most amazing scene, a monumental marble building with the most exquisite architecture, and right there on the landing were a number of couples dancing away. I crossed the road, looked in awe, and then proceeded to put on my dance shoes. One of the dancers who was there showed me where to leave my belongings safely by tying them to a rope.

I managed to enjoy one tanda after another with both locals and visitors until bad luck struck again. One thing I did notice about the style of dance this night was that it was not to the floor or ground, there were a lot of moves going on that were really for performances, not suitable for a milonga.

This is where the story gets gory, one minute I was being lifted up and twirled in the air before doing a sentada, and the next minute I was in incredible pain, I looked down at my right foot and there was blood everywhere. I knew immediately what had happened, I had heard of girls losing their toenails whilst dancing and prayed it would never happen to me. A girl that saw what happened handed me a tissue which I wrapped around my toe, and then I spent the next hour hobbling around Paris looking for an all-night chemist that would recommend what to do next. Although it wasn’t a great end to the evening, it was one of the most spectacular locations I have ever danced at so that in itself made up for all the pain.

One thing that is mind-boggling is that the leader I was dancing with was not in the least bit concerned, he made no attempt whatsoever to help me, he knew I had no internet which really made things more difficult for me. I know that had it been the other way around I would have done everything I could to ensure the person was ok, I would have accompanied them to a clinic or hospital or at the very least gone with them to find a chemist.

Naples

I then travelled to Naples for a few nights and managed to just miss an incredible festival and marathon with two of my favorite dancers, Noelia Hurtado and Carlitos Espinoza.

Salerno

Next on my agenda was Salerno, I really didn’t think I would have an opportunity to dance there because Salerno is a fairly small city that doesn’t have milongas every night of the week. But I was very lucky to make an enquiry which lead to me finding out that there was a milonga that very night, Milonga Tradicional.

I got ready, bandaged my toe and then sat in my room wondering if it was a good idea to go to the milonga, although it was almost two weeks since the incident in Paris I knew that even the slightest touch could be potentially painful. So I took a chance and off I ventured, walking the beautiful little streets of the historic centre in Salerno hoping to find a taxi as Salerno has no Uber. I walked and I walked and I walked and there was not a single taxi in sight, I ended up going to the train station and found a taxi there, the taxi driver explained that the majority of people own their own car so there is very little need for taxis.

The taxi dropped me off right outside the Centro Sociale Salerno (Via Guido Vestuti) at around 10.30pm. Once again, as soon as I closed the door of the taxi I could hear the tango in the air. The organisers here were very welcoming, they went out of their way to make conversation, they asked lots of questions, I was shown to a table and was also told that the €10 cover charge included a drink of my choice. The room was quite large and squarish, it was well attended, small tables and chairs all the way around the room, very dimly lit, unfortunately I forgot to take a photo until the very end when only a few people remained. I enjoyed lots of tandas with some very nice milongueros and overall had a great evening, importantly, without disasters.

Interestingly on two occasions the DJ started playing a tanda (both times it was a milonga tanda), and since no one got up to dance within the first 20 to 30 seconds of the song, he stopped the music and switched over to a completely new tanda.

In a couple of days I will be heading to Cinque Terre before going back home to Sydney. Mission accomplished – well almost!

Written by Beatriz Diaz for www.tangosuraustralia.com (first published October 20, 2019)

-

![]()

Glosas Tangueras / Tango Glosas

I recently discovered that the piece of spoken prose at the beginning of some tangos is called a glosa tanguera or ‘tango glosa’.

A ‘glose’ or glosa is an early Renaissance form developed by poets of the Spanish court in the 14th and 15th centuries. In a glosa, tribute is paid to another poet, and it is made up of two parts, the opening which is referred to as cabeza or ‘texte’ and the second part is the glosa or ‘glose’ itself.

What this means is that four lines of poetry are quoted as an epigraph from another poem or poet. The four lines act a as a refrain in the final line of the four stanzas written by the poet. That is, the first line of the epigraph would be the final line of the first stanza, the second line ends the second stanza, and so on.

In regards to tango, these glosas would be used as a brief commentary of the tango that followed. Interestingly these were not read by the vocalist, but rather by a different artist and it was something that was very common on live radio.

Here are some well known tangos that start with a glosa:

Café Dominguez, Angel D’Agostino, glosa: Julian Centeya

La Cumparsita, Juan D’Arienzo, glosa: Antonio Cantò

Bajo el Cono Azul, Alfredo de Angelis, vocals: Floreal Ruiz, glosa: Néstor Rodi

Nada, Miguel Caló, vocals: Raúl del Mar, glosa: Héctor Gagliardi

Of-course, at a milonga, we don’t always hear these glosas because the DJs either trim them off or they play a different version of the recording that doesn’t include the glosa. Personally, I really enjoy listening to a glosa during a milonga but perhaps I’m biased as I can understand what is being said. I don’t know if the same is true for non-Spanish speakers.

Written by Beatriz Diaz for www.tangosuraustralia.com (first published June 13, 2019)

-

![]()

A follower's conundrum

Recently, whilst at a very popular and busy Buenos Aires milonga a beginner dancer asked me to dance which led to an awkward situation for myself and the beginner dancer.

The situation itself posed a number of interesting questions in regards to etiquette, milonga codes and just basic human interaction.

The leader used cabeceo from a few meters away, I had just arrived and had not had a chance to look at the floor and see the level of dancing of any of the dancers, and in particular I had not watched this man dance. I accepted the dance, stood up, approached the floor where he was waiting and as I did he asked, in Spanish, if the music playing was a milonga. I was taken aback as it was a vals, it was definitely and unequivocally a vals tanda and I was rather dumbfounded, actually, I thought he was pulling my leg! He told me he could dance tango and that his teacher had told him that the milonga was the same but just faster.

And there we stood, not quite knowing what to do. In hindsight this was the moment when I could have declined the dance as we were still standing on the edge of the dancefloor, we hadn’t joined the line of dance.

We started dancing and he was very much a beginner. Normally I have absolutely no qualms about dancing with a beginner, I too was a beginner, we all were. But my conundrum was based around the fact that as a follower, I want to look the best I can, particularly during the very first tanda, in a place where nobody knows me so that they can see what I might be like as a dancer. We are being assessed by the local, experienced milongueros who do not want to be embarrassed whilst on the floor, so that first dance could be crucial to having a good evening.

So on the one hand I was doing the right thing by dancing with this man, but on the other I was doing myself a disfavour and possibly ruining my chances of having some good dances that evening.

The dancer kept asking if he was doing ok, he said he didn’t quite know what to do. I told him to keep it simple, to walk, he did some ochos which he knew how to do but inevitably I ended up doing some reverse leading which I would never do under different circumstances.

At the end of the second vals I thought I couldn’t do it any more, I thanked him and was about to leave but he pleaded ‘you can’t leave me here now’ ‘no me podes dejar aca en la pista plantado’… argh!! So I stayed and danced the final vals.

So many questions… should I have accepted the dance before seeing what he was like as a dancer? Should I have declined whilst we were still on the edge of the dancefloor before joining the line of dance? Once I accepted the dance, was that a full commitment on my part to dance the 3 valses? Is it really that crucial to make a good first impression as a follower? After all, I did end up dancing the entire night, tanda after tanda with beautiful milongueros. And from the point of view of the leader, was he fully prepared? Should he have attended a milonga when he couldn’t distinguish the difference between a vals and a milonga, let alone dance the basics?

Later that night I noticed he was on the floor again and when he left he walked by and waved goodbye with a big smile.

Written by Beatriz Diaz for www.tangosuraustralia.com (first published May 7, 2019)

-

![]()

The milongas of Buenos Aires (Part 1)

The plane touched down in Buenos Aires at 5pm and by 11pm I was on the dancefloor. It sounds extreme but I was so tired a few more hours would have made no difference and besides, I was so excited to be here after a two year absence.

Sueño Porteño, at Centro Region Leonesa

The first milonga was easy, Sueño Porteño, I had been to this milonga before except that it’s now held at another venue (also a venue I’d known from a different milonga). There is an impressive staircase leading up to the first floor, a thick red curtain prevents me from peeking inside, there’s a couple just ahead of me who are paying the entrance fee of $150 pesos (approx. AUD $5). They turn around and say ‘What are you doing here?’ – hilarious, the first people I bump into are Aussies from Sydney, and once inside I find another two Aussies.

I wait for the organiser to sit me down, somewhere half way down the rectangular shaped hall, at a table with ladies only. This room is beautiful, very high ceilings, lovely wooden floor, the DJ is up on the stage and has a screen with the name of the orchestra playing, there is table service so you can order drinks and snacks. Julia Doynel, the organiser, is a real character, she gets on the microphone after every second tanda, she presents both a ladies tanda (women invite a man to dance and in turn give them a chocolate) and a gents tanda (men invite women to dance and in turn give them a single long stem rose).

The music wasn’t arranged in the typical format (TTVTTM, a series of tandas in the following order: tango, tango, vals, tango, tango, milonga). In fact, there were many tandas of vals and only one of milonga. Interestingly, there were also tandas of rock and roll, salsa, and even foxtrot. Oh, and did I mention it was packed?

I had an amazing evening, I danced every tanda except for one, the majority of the leaders were locals, they use cabeceo, and most of the crowd was middle aged and upwards.

Lujos, at El Beso

For the second milonga, I follow a Sydney tanguero’s recommendation and I head to Lujos at El Beso. Once again I have been to this venue before, it’s a much smaller space, it looks a lot more like a nightclub, with a bar area, there are columns within the floor space, the DJ box is way up high, so high I almost didn’t see him. This venue was packed, dancing was reduced to not even a one metre radius, I would say it was closer to just the one tile, this type of dancing is very different, movements are tiny, every step is reduced and minimised.

Here the demographic was similar to the previous night, older, mainly local dancers, a few tourists but not too many, girls all seated along two sides of the floor, men along the other two sides as well as sprawled across the bar area. Cabeceo from all the way across the room. I did see one instance of confusion where two ladies stood up at the same time, which just reminds me why I never ever stand up until I am 100% sure the cabeceo is for me. Phew!

Yira Yira, at La Nacional

Friday night was tricky, aside from the usual 20 milongas or so being held every night, Friday was particularly difficult because there were two good orchestras playing (Romantica Milonguera at La Viruta, and Color Tango at Yira Yira), there was also DJ Vivi La Falce at La Milonga de Buenos Aires whom I’d been wanting to check out for some time. In the end I went to Yira Yira and have no regrets. What a night! Where do I start?

The room: This hall is large but it’s long and narrow, with small tables along the length of both sides of the hall, a stage at one end with group tables, and a bar with group tables at the other end. The host took a while to find seats for everyone waiting to get in, she asked if I had a reservation, I said no, and she found me a fabulous spot, couldn’t be happier. It wasn’t right on the dance floor but I had a good view and could easily cabeceo from my spot. A bar service and snacks (such as empanadas) is available.

The crowd: This crowd was very mixed, about 50% young (early 20’s, very hip tangueros), the rest were middle aged to much older, and too many tourists for my linking. I’m not a snob and clearly I’m a tourist too but I feel that if I’m coming all the way to Buenos Aires I definitely prefer to dance with the local milongueros and for the most part I succeeded, with the exception of a couple of dances.

The DJ and lighting: The music was traditional, the cortinas were a lot of fun with lively music. The lighting was relatively bright during the tandas, but when the cortinas started the large hall lights were dimmed and bright colourful lights flashed much like in a night club, there was definitely a fun/ party atmosphere here.

Taxi dancers: I spotted at least two male taxi dancers. I still don’t get this concept, I know some women want to be assured dances so they pay a dancer to dance with them all night but everyone knows that they are with a taxi dancer – what is the merit in that, and in many ways are they not degrading themselves? Personally I would prefer to take a chance on not being asked than have to pay someone.

The dancing: The level of dancing was good, although not as good as the previous night’s milongas. I did dance with a beginner, not knowing he was a beginner – he had just walked in the door, asked me to dance, and then proceeded to ask if the music playing was a milonga? Ummm… no, it’s a vals. I’m all for dancing with beginners but I really believe that if you don’t know the difference between a milonga, a vals, and tango then it’s too soon for you to be at a milonga.

The floor: It was really crowded with two lines of dance, the outer circle and a very tight long inner circle. Tiny tiny dancing again, on the spot movements. We are spoiled for space in Sydney. One Italian dancer I was dancing with was not so subtly elbowed/ pushed as he wasn’t keeping to his lane, and when the music stopped he was reminded he is to stay within his lane – ouch!

The band: the band came on quite late, at 1am and played for just over an hour. No one danced to the first song (please refer to my last blog about codes).

And finally a little disclaimer. This blog is not intended to offend, it’s simply my views and my experiences of events.

Written by Beatriz Diaz for www.tangosuraustralia.com (first published April 20, 2019)

-

![]()

The milongas of Buenos Aires (Part 2)

Here I continue to share some of my experiences at the milongas in Buenos Aires. Some are a bit of a blur… these milongas don’t get going until very late in the evening and often end at 2am, 3am, even 5am, so between the intensive tango classes and the milongas there was very little time for sleep.

Cachirulo, at Salon Canning

In recent years this had been my favourite milonga, however, it’s no longer held at Obelisco Tango with the fabulous floor. Instead it’s now held at Salon Canning, a historical icon for tango. This was my least preferred night, I’m not sure if it was me, my tired feet, the choice of shoes for that particular floor or the music which didn’t inspire me.

Hector (the infamous organiser) is strict and reminds everyone of tango etiquette including cabeceo, etc. I sat at a table with local women, except for myself and a follower from New Zealand. This milonga has traditional sitting, ambient lighting, bar service with empanadas, and there is a girl at the door selling tango dresses.

Barajando, at Lo de Celia

This milonga really surprised me, I’d heard of Lo de Celia but hadn’t been to any milongas there. This milonga possibly had the least tourists and many older milongueros. I was offered a seat next to the bar, alongside a row of women. As soon as I had my shoes on my feet I was on the floor, cabeceo all the way, except for one dance where I was approached from behind and asked verbally if I would like to dance. I had a fabulous time here. The floor was orderly, the music exquisite, smooth dancers, a tango heaven!

Aurora Milonga, at La Aurora del Tango

This milonga was small, with a suburban feel, locals who take classes earlier on in the evening and stay for the milonga. Everyone is very friendly, I was offered a good seat in the middle of the room adjacent to the dance floor. The floor itself is unusual and somewhat challenging, part of it is made from timber (however, it’s a very rough uncoated timber surface), the rest of the floor is made from ceramic tiles so you end up dancing on both surfaces as the floor is rectangular and each surface covers approximately 50% of the dance area.

I had an opportunity to dance with the DJ which was quite fascinating, he was telling me about some interesting discoveries he’d made and some of his favourite 1950’s Biagi. A huge portrait of Carlos Gardel hangs at an angle from the ceiling. There is a bar at the back where locals sit and chat. The lighting here was fairly dim, it was an informal evening.

Parakultural, at Salon Canning

Back at Salon Canning, this time to see an orchestra named ‘Los Herederos del Compas’, I would go back just to see this orchestra perform again, they were simply amazing, they only play D’Arienzo as the orchestras’ name implies, the energy levels were incredible, it’s difficult to describe, listening and dancing to their music was an absolute joy.

Cachirulo, at El Beso

I’m back at El Beso for the third time in as many days, it seems everyone ends up at El Beso, whether you’re taking classes with Maria Plazaola, doing the afternoon practicas or going to the late night milongas, it’s a very popular venue with both locals and tourists alike.

When I walk in Hector greets me at the door and immediately takes a liking to me, he grabs my hand and walks me across to the other side of the room, orders someone to move and then gives me a spot adjacent to the floor but at the end of the row of women. About 10 minutes later he comes over again and asks me to move to the centre, still adjacent to the floor but in prime position for cabeceo.

After seven nights of dancing you begin to see familiar faces. There are too many tourists here tonight but it’s my final night in Buenos Aires so it has to end on a high. I decided to wear a pair of brand new shoes so that their soles would have dust from a BA dancefloor… filled with wonderful memories. I leave the milonga a very happy girl.

Written by Beatriz Diaz for www.tangosuraustralia.com (first published April 28, 2019)

-

![]()

Tango etiquette and the milonga codes

In a little over a week I’ll be heading to Buenos Aires and Montevideo so what better time than now to re-visit the milonga codes which are prevalent in many of the milongas in Buenos Aires as well as across the world. This is a list of recommended Do’s and Don’ts, of-course not all apply to all venues, some milongas are far stricter than others, some are filled with young people, whilst others have an older, more traditional demographic of visitors, locals and old time milongueros.

Some of these codes have been around for over 100 years so they may seem antiquated, however, they work. So without further ado, here are some of the most popular codes which still apply today.

GENERAL CODES

Often, each milonga has its own codes, take time to observe the floor and the dancers when you arrive, some milongas even have a sign on the wall with their codes printed on them.

The music is arranged in ‘tandas’, sets of songs typically arranged in groups of 3, 4 or 5 songs. Each set is called a ‘tanda’, and each ‘tanda’ is separated by a piece of non-tango music which is called a ‘cortina’ or ‘curtain’. The ‘cortina’ indicates the end of a ‘tanda’, these generally last between 30 and 60 seconds. Furthermore, the music is generally arranged in the following manner: two tango tandas, one vals tanda, two tango tandas, one milonga tanda, and so on (TTVTTM, TTVTTM…).

During the short interval between each song within a ‘tanda’ (approximately 5 seconds) the embrace is broken.

The ‘cabeceo’ or ‘nod’ is used to ask a woman to dance. This is done from a distance, the man will look at a woman and indicate with a nod or ‘cabeceo’ that he would like to dance with her, the woman then has two choices, she can ignore the look and take her gaze elsewhere or she can accept the dance by smiling and nodding back. She then waits for him to approach the table. Ladies, do not stand up off your seat until you are completely certain that he was in fact asking you to dance and not someone immediately behind you.

It’s considered rude to speak whilst dancing, and chewing gum is frowned upon.

If the woman wishes to dance she mustn’t be seen with a partner, unless her partner first gets up to dance with another woman. Often in Buenos Aires the men sit on one side of the room, the women sit across the other side of the floor, whilst couples/ friends/ etc remain at the other ends of the room.

If you do venture up to a couple and ask the lady for a dance, please acknowledge the existence of the partner.

You must never leave the floor before the end of the ‘tanda’, it is seen as rude to walk off after a couple of songs without finishing the entire ‘tanda’.

It is customary for the man to walk the woman back to her table.

If there is an orchestra, you don’t dance to the first song.

Personal hygiene is very important.

FLOOR CRAFT – these are of particular importance to allow for fluidity on the dance floor as well as to avoid injuries, arguments, etc.

One person leads, the other follows. I have been at milongas where same sex couples were prohibited from dancing and were asked to leave.

The line of dance is anti-clockwise.

There are several ‘lanes’ from the outermost lane to the inner circle.

The most experienced dancers are in the outermost lane, and the less experienced dance in the middle. The idea behind this is that the more experienced dancers can show off their skills to people sitting at tables around the dance floor and it allows for more fluid movement across the floor. The less experienced dancers remain in the inner circles or centre so as to not disturb the fluidity of movement in the outer lane.

You must not change from one lane to the other or cross into the path of another lane. If the couple ahead aren’t moving than you need to dance on the spot and wait until they move.

You must not over take a couple ahead of you, you should wait until they move.

Do not close in on the couple in front so much so that they have no space to dance in.

Should there be an incident/accident, apologise. The apology needs to come from the leader who is the one who makes the decision on the use of the space. The apology can be a simple gesture or a verbal apology once eye contact has been established.

Avoid going backwards.

Avoid dancing in the spot for more than one or two beats, assuming there is space ahead.

Do not walk across the dance floor to get from A to B.

A leader must stop a move if there’s a chance of collision.

Written by Beatriz Diaz for www.tangosuraustralia.com (first published April 7, 2019)

-

![]()

The milonga rhythm

A couple of weeks ago I was invited to write a blog about the milonga rhythm, and given the milonga classes being held in Wollongong over the coming few weeks it seemed like the perfect opportunity, so I agreed to do some research on the subject and was surprised with what I found.

As way of introduction, the milonga rhythm is a style of folkloric music that is shared across the River Plate in both Uruguay and Argentina. I discovered that when using the word ‘milonga’ to describe the rhythm, there are in fact two variations.

Firstly the original style of milonga which was played by the gauchos (horsemen or cowboys) that travelled from town to town, traditionally just on the outskirts of the city. They gathered with other gauchos and played their guitars, always improvising the music whilst at the same time creating spoken poetry to accompany the music. This style of milonga is the ‘milonga campera’ or ‘country milonga’.

The origins of the ‘milonga campera’ style of milonga are often debated but it is said that it contains African elements within the rhythm as well as influences from various styles of dance that arrived to the region of Buenos Aires and Montevideo from Peru, Spain, Brazil and Cuba. During this time, the styles of music varied as they travelled backwards and forwards between Latin America and Europe, picking up adaptations from the various regions as time went on.

Towards the late 1800s musicians of the time went to the milongas (in this sense, I am referring to the place where people came together to dance), and began to adapt the music so that it became more danceable, leaving behind the improvised spoken poetry and focusing more on the music. The music itself became more stylised, adding piano, mixing this rhythm with the music that was popular at the time, the tango, which at the same time had influences from other styles such as Habanera and Candombe.

This transition and transformation led to the second style of milonga which is referred to as ‘milonga ciudadana’ or ‘city milonga’.

In 1931 the style of milonga rhythm that we enjoy dancing to at milongas today was created by Sebastian Piana and Homero Manzi with ‘Milonga Sentimental’. Here is a version by Carlos Gardel recorded in 1933.

And here are Miguel Angel Zotto dancing with Daiana Gúspero to ‘Reliquias Porteñas’.

Written by Beatriz Diaz for www.tangosuraustralia.com (first published February 23, 2019)

-

![]()

Tango: Poema

You will often hear the tango Poema (Poem) played at milongas around the world. The music was composed by Mario Melfi and the lyrics were written by Eduardo Bianco. Francisco Canaro recorded the following version in 1935 with vocalist Roberto Maida. Canaro, a violinist, was born in Uruguay on 26th November 1888 and died in Argentina on 14th December 1964.

And here is a modern version by Orquesta Romantica Milonguera with a great video to match.

ENGLISH:

It was a dream of sweet love,

hours of happiness and loving,

it was the poem of yesterday,

that I dreamed,

of gilded color,

vain chimeras of the heart,

it will not manage to never decipher,

so fleeting nest,

it was a dream of love and adoration.When the flowers of your rose garden,

bloom again ever so beautiful,

you’ll remember my love,

and you will come to know,

all my intense misfortune.Of that one intoxicating poem,

nothing is left between us,

I say my sad goodbye,

you’ll feel the emotion,

of my pain…*Source: www.planet-tango.com

SPANISH:

Fué un ensueño de dulce amor,

horas de dicha y de querer,

fué el poema de ayer,

que yo soñé,

de dorado color,

vanas quimeras del corazón,

no logrará descifrar jamás,

nido tan fugaz,

fue un ensueño de amor y adoración.Cuando las flores de tu rosal,

vuelvan mas bellas a florecer,

recordarás mi querer,

y has de saber,

todo mi intenso mal.De aquel poema embriagador,

ya nada queda entre los dos,

doy mi triste adiós,

sentiras la emoción,

de mi dolor…Written by Beatriz Diaz for www.tangosuraustralia.com (first published January 30, 2019)

-

![]()

Juan D’Arienzo, his orchestras and singers, through the years

El Rey del Compás

Juan D’Arienzo was born on 14th December 1900 and died on 14th January 1976 in Buenos Aires. He played violin with Angel D’Agostino from a very early age and formed his own orchestra in 1928. D’Arienzo recorded with the record labels Electra in 1928-1929 and Victor from 1935-1975.

In 1935 D’Arienzo’s orchestra consisted of 3 bandoneons, 3 violins, piano and double bass, the musicians were:

Domingo Moro, bandoneón

Faustino Taboada, bandoneón

Juan Visciglio, bandoneón

Lidio Fasoli, piano

Alfredo Mazzeo, violin

Leon Zibaico, violin

Domingo Mancuso, violin

Rodolfo Duclos, double bassThey did a total 10 recordings with the record label Victor, including Desde el Alma on 2nd July 1935. (Click here to view video).

When pianist Rodolfo Biagi joined the orchestra in 1935 everything changed, he introduced a change in the rhythm of the music which would prove irresistible to dancers and this change was what marked the new style for D’Arienzo going forward, one which would provide him with the huge success that he attained during the Golden Age of tango.

Aside from Biagi replacing Lidio Fasoli on piano, from 1935 until 1938 there were other changes to the orchestra with the addition of two more bandoneons and a fourth violin. The orchestra was now made up by the following musicians:

Domingo Moro, bandoneón

Faustino Taboada, bandoneón

Juan Visciglio, bandoneón

Jose Della Rocca, bandoneón

Adolofo Ferrero, bandoneón

Rodolfo Biagi, piano

Alfredo Mazzeo, violin

Leon Zibaico, violin

Domingo Mancuso, violin

Francisco Mancini, violin

Rodolfo Duclos, double bassThe singers were: Walter Cabral, Enrique Carabel, and Alberto Echagüe.

They did a total of 66 recordings with the record label Victor, including El Flete on 3rd April 1936 (Click here to view video).

In 1938 Biagi departed to form his own orchestra and was replaced by pianist Juan Polito. Alberto Echagüe continued on and together they did 40 recordings with the record label Victor from 1938 to 1939, including Nada más on 8th July 1938 (Click here to view video) and No mientas on 28th December 1938 (Click here to view video).

They had the perfect combination but in 1940 when Juan Polito left the orchestra, he took every musician with him, including Alberto Echagüe.

D’Arienzo very quickly assembled a new orchestra and so for the period of 1940 until 1950 we see the arrival of a very young Fluvio Salamanca on piano and Hector Varela on violin. The following were the musicians during that 10 year period:

Eladio Blanco, bandoneón

Alberto San Miguel, bandoneón

Hector Varela, bandoneón

Jorge Ceriotti, bandoneón – replaced by Pinotti

Jose Di Pilato, bandoneón

Salvador Alonso, bandoneón

Fluvio Salamanca, piano

Cayetano Puglisi, violin

Blas Pensato, violin

Jaime Ferrer, violin

Clemente Arnaiz, violin

Olindo Sinibaldi, double bassThe singers were: Alberto Reynal, Carlos Casares, Hector Maure, Juan Carlos Lamas, Alberto Echagüe, and Armando Laborde.

Together they did a total of approximately 255 recordings with the record label Victor including:

Rie Payaso, 22 agosto 1940 (Carlos Casares). Click here to view video.

Vidas marcadas, 29 abril 1942 (Alberto Reynal). Click here to view video.

Amarras, 21 julio 1944 (Hector Maure). Click here to view video.

Y entonces lloraras, 30 abril 1947 (Armando Laborde). Click here to view video.

D’Arienzo’s orchestras are well known for their lively beat and strong rhythm both of which make the music ideal for dancing. There are moments when everything stops and the piano plays in the background, or moments when the bandoneons take centre stage and they are the star of the show as can be seen is this video and years later in this example.

Juan D’Arienzo’s energy can easily be observed, he gives so much in his performance and at the same time passes on that energy to the musicians, he appears to demand a lot from them as he stands there watching, listening, making remarks with very expressive facial gestures.

The members of the orchestra were very young, some as young as 18 and many of them in their early 20s it’s no wonder they could follow this pace of music.

He considered the piano as the base instrument, with beautiful variations performed by the bandoneons, all leading to a constant rhythm (in the most part), the arrival of Biagi made all of this possible, bringing back the 2×4 and reviving many of the tangos from the Guardia Vieja such as El Entrerriano, Derecho Viejo, Hotel Victoria, El Choclo, etc.

D’Arienzo was quoted as saying “The way I see it, tango is, above all, rhythm, nerve, strength and character. The old tango, the tango from the old guard (Guardia Vieja) had all of this, and we must try to never lose this.” He continued to enjoy huge success with dancers, playing to huge crowds at packed venues.

“The base of my orchestra is the piano. I believe it to be irreplaceable. When my pianist, Polito fell ill, I replaced him with Jorge Dragone. If something should happen to him I have no solution. Then the violin with a fourth string appears as a vital element. It must sound like a viola or cello. I integrate my group with the piano, the double bass, five violins, five bandoneons and three singers.

D’Arienzo stayed true to his style through the golden age of tango, although there were times that he had to adjust to the singers. For example, when Hector Maure joined in 1940 it was difficult for him to keep up with the speed of the orchestra so some adjustments had to be made to the way the music was played, and while Hector Maure is considered to have been the best singer the orchestra ever had it may not have been the best choice for their style.

Alberto Echagüe

Alberto Echagüe was born in Rosario on the 8th March 1909 as Juan de Dios Osvaldo Rodríguez Bonfanti. Echagüe had three phases with D’Arienzo, 1938-1939, 1944-1957, in 1968 he travelled to Japan with D’Arienzo and continued to record together until 1975, this being the third and final phase.

Echagüe was able to keep up the speed with D’Arienzo, and while technically he wasn’t a great singer, he did have a great fit with the style of D’Arienzo. He was used as an estribillista or chansonnier and would sing a small portion of the lyrics, usually the chorus towards the end of the song. In this sense the singer was regarded as another instrument, and not the star of the orchestra.

His voice had a street style, ‘arrabalero’ with a predominant use of ‘lunfardo’ language which only added to his style. He died in Buenos Aires on 22nd February 1987.

Written by Beatriz Diaz for www.tangosuraustralia.com (first published December 31, 2021)

-

![]()

The golden age of tango

The Golden Age of tango is the period from the late 1930’s to the mid 1950’s, although some would argue that the true Golden Age of Tango is the decade of the 1940s.

It is referred to as the Golden Age of Tango because it is when tango was at its highest in terms of popularity. Tango became both the music and the dance for the masses in the city of Buenos Aires during the 1940s.

At the time, tango wasn’t restricted to a certain age group but rather attracted all generations, from children, to their parents and grandparents. You could listen to tango on the radio, and due to the popularity of records which became more affordable and accessible to the general public, many would also listen to tango at home. Tango orchestras became increasingly popular and played every night of the week across clubs in the city and city fringes, in cinemas, cafes, bars, etc.

Tango was a lifestyle and a pastime for the masses and it was driven by a number of important factors, including: population growth; infrastructure; the technological means; and finally a change in the dynamics of the music. But to truly understand how these factors impacted the growth of tango we need to go back in time.

The Great Depression and economic crisis that started with the stock market crash of October 1929 had a huge impact on Argentina, as demand in Europe and the United States for its farm exports suddenly declined. From the 1930s Argentina adopted a strategy of import substitution designed to convert it into a self-sufficient country in industry as well as agriculture. Population growth from the provinces into Buenos Aires grew form approximately 8,000 people per year to 72,000 per year in the mid 1930’s to 117,000 in the mid 1940’s. By the mid 1940’s the urban area held 56% of all industrial establishments and 61% of the total workforce of the country.

Population growth meant that housing and infrastructure grew too. During this period there was little differentiation in terms of leisure activities for adults vs. teens vs. children, there was a mix of generations in most social activities – this was the norm. Local clubs began to open in the neighbourhoods and basketball was huge in Argentina at the time. These presented the perfect meeting spot for dances and other social gatherings.

At this time Buenos Aires had the population and the venues, next came the technology that allowed the music to be spread far and wide via radio which experienced exponential growth during the 1930’s, as well as well-known publications such as ‘La Canción Moderna’, ‘Radiolandia’, and ‘Antena’, and let’s not forget the establishment of large radio studios such as ‘Radio del estado’, ‘Radio El Mundo’, and the filming of the first film with sound (please see previous post to read more about the film).

The final element was a change in trend in the music with the birth of the huge dance orchestras of the late 1930s such as D’Agostino, D’Arienzo, Di Sarli, Pugliese, De Angelis, Caló and Trolio. This music was less for listening and more for dancing.

All of this coincided with the Great World War, all the while Argentina remained neutral which had a huge positive financial impact on the country.

What factors led to the decline of tango?

As with the rise in tango, several factors led to the decline in the popularity of tango. Factors such as the end of World War II, local politics, international and local economy, the rise of capitalism, all had an important role to play. The very thing that drove Argentina to huge success at the start of the war was what was impacted negatively on the economy, worldwide agricultural demand was far more competitive with the USA, Canada and Australia back in the picture.

From a political perspective, directly related to art and culture, there was censorship of the language and in turn censorship of Lunfardo as well as the exile of actors and musicians as a direct result of political developments.

In addition, in 1950 there was a rise in sales of folk music – for the first time surpassing sales of tango music, in 1950 the largest discotheque opened in Buenos Aires with organisers ensuring they had the latest music by travelling several times a year to both the UK and the USA.

From 1951 TV also played a role as did consumerism lead by the USA. Teens wanted to differentiate themselves from other generations by dressing differently and listening to different music than that of their parents or grandparents. It was at this point that tango orchestras introduced changes to the music, in an attempt to bring it in line with what was happening around them (eg. Rock n roll). But it was to no avail, the younger generations were no longer interested in tango, in any form, and thus moved to rock and other genres of music.

There’s also the 1955 coup d’état which leads to repression and persecution and Argentina is driven into a deeper crisis. In the early 1960s Channel 13 launches ‘Club del Clan’ a music program which becomes incredibly successful and launches the careers of many artists including Palito Ortega. This single event is often attributed to the decline in tango but it was the collision of the above factors that ultimately led to the demise of tango from the lofty heights it enjoyed in the 1940s.

Written by Beatriz Diaz for www.tangosuraustralia.com (first published December 31, 2021)

-

![]()

The survival of tango through challenging times

A little bit of history

If tango were personified, it would be a fighter and a survivor.

Tango survived the great depression of 1929 and restrictions imposed at the start of the 1930s. It wasn’t until the government of Juan Peron that tango became fashionable again, only to suffer yet again during the 1950s after a series of dictatorships banned public gatherings and Rock & Roll emerged in the USA and Europe.

In the 80s and early 90s it started to re-surface again thanks to the opening in Paris and Broadway of the show Tango Argentino, and by Miguel Angel Zotto and Milena Plebs who captivated the world with their shows.

Finally, on the 31st of August 2009, UNESCO approved a joint proposal by Argentina and Uruguay to include the tango in the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists. Since then it has been growing and spreading around the world and it’s enjoyed by people of all ages.

The impact of social distancing on tango

When COVID-19 spread from city to city and exploded across the globe, everyone was affected, including all those people who work in the tango industry and who enjoy social dancing on a regular basis.

To know tango is to understand how it can slowly and quietly seep into your bloodstream, through your veins and into your heart, it can become not only an obsession and a passion but also an addiction, and for many it’s a form of therapy – with well documented social, physical and emotional benefits.

In March 2020 tough decisions needed to be made by schools, organisers and social dancers before the government of Australia stepped in and made the decisions for us. Isolation. Social distancing. Closure of clubs. Confinement. Quarantine. Pandemic. No public or private gatherings. Hundreds of thousands of deaths across the globe. Words and concepts are difficult to fathom.

Keeping tango alive

They say that necessity is the mother of invention and that is precisely where creativity stepped in to keep tango alive in our homes and in our hearts during these challenging times.

From local and international virtual milongas, festivals and classes; online webinars by prominent DJs and historians; Zoom performances by solo musicians, singers, and well-known tango orchestras; and even a 48-hour round-the-world milonga broadcast live over the radio, which made news headlines around Europe and South America.

The time gifted to us by the lock-down measures meant we suddenly had the time to practice, listen to music, read, dust off our records, watch documentaries and old films on YouTube, and discover even more. It’s times like these that I remind myself that when it comes to tango ‘Solo se que no se nada’, in other words ‘I know that I know nothing’.

Of-course, those most affected are dancers and teachers, but there is a whole other group of tango lovers who do not dance, they simply enjoy listening to tango music, many are collectors, for them, it would be business as usual in their homes.

The big question remains: when will we be able to dance again at a milonga? In Argentina and Uruguay many believe it won’t be until 2021; as for Australia, I only hope that it’s very soon.

Until then, we’ll continue dancing in our living rooms, in our minds and in our hearts.

Written by Beatriz Diaz for www.tangosuraustralia.com (first published May 25, 2020)